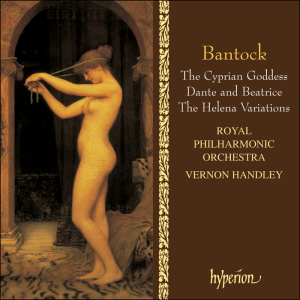

Bantock: Cyprian Goddess Symphony, Etc / Vernon Handley, Royal Philharmonic Orchestra – Tonträger gebraucht kaufen

Möchten Sie selbst gebrauchte Tonträger verkaufen? So einfach geht's …

Verkäufer-Bewertung:

100,0% positiv (582 Bewertungen)

dieser Tonträger wurde bereits 1 mal aufgerufen

dieser Tonträger wurde bereits 1 mal aufgerufen

Versandkosten: 15,00 € (Deutschland)

gebrauchter Tonträger

* Der angegebene Preis ist ein Gesamtpreis. Gemäß §19 UStG ist dieser Verkäufer von der Mehrwertsteuer befreit (Kleinunternehmerstatus).

Dieser Artikel ist garantiert lieferbar.

Künstler/in:

EAN:

Label:

Hyperion,DDD,95

Zustand:

wie neu

Spieldauer:

69 Min.

Jahr:

1995

Format:

CD

Gewicht:

120 g

Beschreibung:

Album: NEU und EINGESCHWEISST (OVP) SEALED

Bantock: The Cyprian Goddess, Dante And Beatrice / Handley

Release Date: 11/21/1995

Label: Hyperion Catalog #: 66810 Spars Code: DDD

Composer: Granville Bantock

Conductor: Vernon Handley

Orchestra/Ensemble: Royal Philharmonic Orchestra

Number of Discs: 1

Recorded in: Stereo

Length: 1 Hours 9 Mins.

Works on This Recording

1. Symphony no 3 "The Cyprian Goddess" by Granville Bantock

Conductor: Vernon Handley

Orchestra/Ensemble: Royal Philharmonic Orchestra

Period: 20th Century

Written: 1938/1939; England

Date of Recording: 05/1995

Length: 24 Minutes 23 Secs.

2. Variations for Orchestra on the theme HFB "Helena Variations" by Granville Bantock

Conductor: Vernon Handley

Orchestra/Ensemble: Royal Philharmonic Orchestra

Period: 20th Century

Written: 1899; England

Date of Recording: 05/1995

Length: 19 Minutes 25 Secs.

3. Dante and Beatrice by Granville Bantock

Conductor: Vernon Handley

Orchestra/Ensemble: Royal Philharmonic Orchestra

Period: 20th Century

Written: 1901/1910; England

Date of Recording: 05/1995

Length: 25 Minutes 0 Secs.

Notes and Editorial Reviews

'Hyperion's third collection of orchestral works by Sir Granville Bantock, a composer who rivalled Elgar in his day, is quite simply superb' (The Scotsman)

'Outstanding. A sumptuous wallow for all unashamed Romantics' (BBC Music Magazine)

'Full marks, Hyperion - now we can all wallow once more. Worth the price for the sumptuous sound alone!' (BBC Music Magazine)

'Just as good as its predecessors. Roundly recommended' (Fanfare, USA)

'The finest large symphonic recordings of the decade. The burnished colors of Bantock's singular music - moody, quirky, haunting - glow under the direction of Vernon Handley' (Fi, USA)

Pressestimmen

I. Lace im BBC Music Magazin 1 / 96: "Diese Ver- öffentlichung ist herausragend: ein Schwelgen in unverhohlener Romantik. Alle drei Stücke bezeugen Bantocks Meisterschaft der Orchester- behandlung, besonders sein markanter vielstim- miger Blechbläser-Satz. Handley und das RPO lieben dieses Repertoire hörbar und musizieren mit Inbrunst und Virtuosität."

Product-Information:

Sir Edward Elgar described Bantock as having ‘the most fertile musical brain of our time'. The Cyprian Goddess, Bantock's Third Symphony, was written as he crossed the Pacific Ocean. The music plays continuously, but consists of a variety of contrasting sections, and the feeling of a story or succession of images is striking. Bantock's dream of Aphrodite and of a happier time is vivid and gripping. The world-famous Royal Philharmonic Orchestra and Vernon Handley here see their third in a series of Bantock recordings, all of which have met with consistent praise.

Introduction

The Edwardian period, and indeed the late 1890s, is fascinating for the student of British music. It saw the first appearance of what we now know as an extended repertoire of distinctively English music (even though the composers of much of it were in fact Irish or Scottish and some of the landscape that inspired them was on the Welsh border!). The big name as far as we are concerned was, of course, Elgar. But at a time when provincial centres of music were of major importance, Granville Bantock, associated with Birmingham from 1900 to 1934, was regarded by some as comparable with Elgar. It was Neville Cardus, no less, who wrote: ‘Those of us who were then “young” and “modern” regarded Bantock as of much more importance than Elgar … Bantock was definitely “contemporary”.' Indeed it was Elgar himself who referred to Bantock as ‘having the most fertile musical brain of our time'.

Bantock first achieved fame as a conductor and as the champion of his British contemporaries, though it was not only British music that he pioneered. In particular, he was an early advocate of Sibelius and is the dedicatee of the Finnish master's Third Symphony. Soon he was also known as a fluent composer of considerable individuality.

Bantock was born in London in 1868, the son of a well-known surgeon. His youthful passion for music parallels the story familiar from the lives of many composers—of overcoming parental opposition. In Bantock's case his father's chosen career for him was the Indian Civil Service, and later, chemical engineering. Music, of course, prevailed and in 1888 he spent a summer holiday in Germany soaking up Tristan and Parsifal, and then started at the Royal Academy of Music as a composition pupil of Frederick Corder contemporary with Joseph Holbrooke. Corder would later teach Bax, York Bowen and Eric Coates, among many others.

Music poured from the young Bantock and though at first both Tchaikovsky and Strauss were noticeable as models, a very personal use of both voices and the orchestra enabled him to establish himself during the first decade of the century as an individual composer of personality and stature. Bantock was an illustrator in music. He was never lost for an apt musical image, and at his peak produced many arresting, colourful scores. This was when he was working on his massive setting of the complete text of Fitzgerald's Omar Khayyám, and the music he wrote at this time shares Omar's teeming invention and flamboyant scoring for both voices and orchestra. Between 1900 and 1914 Bantock produced, counting the three parts of Omar Khayyám separately as they were performed, seven extended works for chorus and orchestra, two extended orchestral song cycles (a third was orchestrated later), and more than a dozen colourful orchestral scores as well as voluminous songs and choral music.

After the First World War a new generation of brilliant composers emerged and Bantock began to appear old hat; indeed, by the time of the Second World War he was widely regarded as a ‘has been' by the younger generation, and if it had not been for the efforts of Cyril Neil, the managing director of the publisher Paxton, he would have had no encouragement and little income. Neil issued many short works that he specially commissioned on Paxton's own record label—really just a mood-music catalogue. While it included one or two fine works such as the Celtic Symphony and the frankly Sibelian Four Chinese Landscapes, the general critical effect was to underline how Bantock the composer had become a back number. Certainly it was no time to be making long-term assessments. Only now with the perspective of over fifty years and the advantage of fine performances can Bantock's quality, and the colour and personality of his music be fully appreciated.

Bantock gained considerable experience during 1894/5 conducting one of George Edwardes's variety companies on a world tour, particularly featuring Sydney Jones's A Gaiety Girl. On his return he was appointed Director of Music to the Tower Orchestra, New Brighton (a then fashionable resort across the Mersey from Liverpool) from 1897, where his expansion of the band and championship of British and other contemporary music won him a national reputation. In 1900 he secured the post of Principal of the Midland School of Music in Birmingham and in 1908 he succeeded Elgar as Peyton Professor of Music at Birmingham University. He was thus firmly established as a figurehead of British music outside London.

The twentieth century was a notable time for the development of the British symphony (indeed all symphonies). Paradoxically it was also the time when the avant-garde of succeeding generations solemnly informed us that the symphony was dead—and then went on to revitalize it in many startling ways! Bantock's first attempt at a symphony was probably a student exercise; a Symphony in C (1888) of which the full-score manuscript of a first movement and a scherzo and trio survives. Later came the Hebridean (1915/16) and Pagan (1923–1928) symphonies, and after these The Cyprian Goddess (1938/9) and the Celtic Symphony (1940). Bantock also used the term ‘symphony' for several vocal works, though he obviously did not consider them as forming part of any symphonic cycle or he would not have enumerated The Cyprian Goddess as number three. The first was Cedric and Aelfrida, subtitled ‘a dramatic symphony for orchestra and four voices', a sort of concert opera, dated 20 August 1892 and written when he was still a student. Later came Christus, ‘a festival symphony in ten parts'—a vast choral cycle that was never finished. Perhaps most intriguing were the choral symphonies for huge unaccompanied choirs written at the height of his powers before the First World War. These were Atalanta in Calydon (dated 29 September 1911), Vanity of Vanities (1913) and A Pageant of Human Life (3 August 1913). There are also a few sketches for an aborted Ossianic Symphony for voice and accompaniment. So Bantock was not only involved in the symphony as a form but also took the widest and most all-embracing view of what constituted the symphony. ‘The symphony must be like the world. It must embrace everything', Mahler is reputed to have said to Sibelius in a celebrated aphorism, a view to which Bantock must surely have subscribed.

One March afternoon in 1896 the twenty-eight-year-old Helena von Schweitzer called to have tea with an old lady. There was a third guest: ‘His head was leonine, with its massive formation and tawny colouring, and his eyes were remarkable, scintillating with vivid life, windows to an intense inner existence. He was massive in build also, and golden-bearded at a time when all the fashionable men-about-town were moustachioed with monotonous regularity.' Thus Granville Bantock's future wife later remembered how she first met her husband. She went on to describe his polymath interests: ‘The talk was as unconventional as the surroundings were prosaic. It fell on the ears of one listener like the sound of water on a parched land. Science, literature, art and travel were discussed in a broad-minded spirit, very foreign to that period of many taboos. The hostess drew the shy listener into the conversation, and at the end of this miniature symposium, she found herself committed to the task of writing thirty-six lyrics, to be set to music by the young composer, for such he was' … ‘On a slip of paper he sketched out his scheme for a series of thirty-six Songs of the East, each set of six to be devoted to an oriental country. He would provide books on the subject, further discussion was arranged for the following week, and the whole was completed with tornado-like swiftness which soon became familiar.'

They were married in 1898, and the following year he wrote Helena, variations on a theme derived from the initials of his wife's name (HFB: in German musical notation, B natural, F, B flat). The piano score is dated 27 October 1899; Granville and Helena were both thirty-one. In less than a year the music was published by Breitkopf & Härtel. Printed on the flyleaf the composer wrote: ‘Dearest Wife! Accept these little Variations with all my heart's love. They are intended as an expression of my thoughts and reflections on some of your moods during a wearisome absence from each other.'

Elgar's Enigma Variations had been first performed in London on 19 June 1899 and created a great stir. Bantock had invited Elgar to conduct a concert with his orchestra at New Brighton, and soon afterwards Edward and Alice Elgar (not yet Lady Elgar) came to stay; Elgar's wife would have been fifty. Helena Bantock noted with astonishment ‘no less than seven hot water bottles being filled for his bed, on the occasion of Elgar complaining of a slight chill'. On 16 July Elgar conducted the concert, including Enigma, and one cannot imagine Bantock being other than thrilled. It seems highly probable that Bantock then impulsively set out to write his own variations, albeit based Pauline-like on his wife's moods rather than his various friends. It was his first orchestral work in his mature style. Could it be that in emulating Elgar by ending in high spirits it was not only Helena he was celebrating in the Finale. First performed in Antwerp on 21 February 1900 where Bantock had been asked to conduct a concert of British music, the Variations received their first British performance, conducted by the composer, on 25 March in the Philharmonic Hall Liverpool.

Dante and Beatrice was originally written (as Tone Poem No 2) in the summer of 1901 and performed at New Brighton and also in Birmingham at a Halford Concert. A commentator on the first version, which is now lost, pointed out that when Bantock revised it (the new score is dated 31 July 1910), little alteration was made in the music apart from the blending of the sections into a continuous fabric. The early version was in six sections, and it may be helpful to have the titles as a guide to the main episodes in the later version. These were: ‘Dante', ‘Strife of Guelphs and Ghibellines', ‘Beatrice', ‘Dante's vision of Hell, Purgatory and Heaven', ‘Dante's exile', and ‘Death'. In the revision of 1910 recorded here, Bantock styles his score a ‘psychological study' intending to evoke states of mind rather than describe individual episodes in detail.

The music opens with an introduction which presents the two important themes—Dante's quietly in unison and, after a climax, Beatrice's theme appears against a yearning extension of Dante's motif. The themes are developed as finally they are combined. At the climax of the development the music becomes wilder—firmly based on diminished sevenths—with a cataclysmic outburst, the depiction of the ‘Vision of Hell, Purgatory and Heaven' in the earlier version. This leads to the extended lyrical closing section of the work, the chromatic harmony and brilliant handling of a large orchestra creating an ecstatic mood distinctive of its time. Soon Dante hears of Beatrice's death (‘poignant grief') and dies still transfigured by his love for her. Dedicated ‘To my friend Henry J Wood', the score is prefaced by the quotation ‘L'amor che move il sole e l'altre stelle' (‘The love that moves the sun and the other stars') from Il Paradiso. The first performance was at Queen's Hall on 24 May 1911 during the London Music Festival in the Coronation season. It cannot have been entirely satisfactory for Bantock as it was the same concert in which Elgar's Second Symphony was first heard. Ticket prices were sky-high and the critics were there to hear Elgar—about whom they wrote at length—and not his illustrious Birmingham contemporary.

After the War Bantock remained in Birmingham until 1934, composing a variety of works and in particular briefly achieving some celebrity for his two vast choral works The Song of Songs (broadcast on 11 December 1927) and Pilgrim's Progress (commissioned by the BBC a couple of years later), the latter before Vaughan Williams was generally associated with Bunyan or Pilgrim. However, Bantock's new works were less and less heard in concerts and were no longer seen as representing the new. Though the Pagan Symphony was first performed in 1936, Bantock's star as a composer was no longer in the ascendant in spite of his knighthood in 1934.

In the 1930s he undertook examining tours overseas for Trinity College of Music and it was while on one of these that he wrote the The Cyprian Goddess, his third symphony, which he subtitled ‘Aphrodite in Cyprus'. Written while crossing the Pacific, the manuscript full score is dated ‘12 January 1939 Pacific Ocean. Suva (Fiji)'.

Bantock's love affair with languages led him to study not only Latin and Greek, but also Persian. The Pagan Symphony had taken its cue from the second book of Horace's Odes, and the opening of Ode XIX concerning Bacchus. Aphrodite is, of course, the Goddess of Love, whom he had invoked so memorably before in the Sappho Songs for contralto and orchestra. Now in The Cyprian Goddess he prefaces the score with the two Latin verses of Ode XXX in the first book, as well as a photograph of the statue of the Venus de Milo from the Louvre.

O Venus regina Cnidi Paphique

Sperne dilectam Cypron et vocantis

Ture te multo Glycerae decoram

Transfer in aedem.

Fervidus tecum puer et solutis

Gratiae zonis properentque Nymphae

Et parum comis sine te Juventas

Mercuriusque.

Venus, queen of Knidos and Paphos,

quit thy favoured Cyprus and come

to the fine temple of Glycera which

calls you with much incense.

Let the passionate child, the Graces

with their girdles untied, the nymphs,

Youth, all the less attractive without you,

and Mercury hasten with you.

The music plays continuously, but consists of a variety of contrasting sections, and the feeling of a story or succession of images is striking. Why Bantock was never commissioned to compose for the films when he writes so cinematographically is a mystery. Bantock gives us no detailed programme, but from time to time he writes a classical quotation (in English translation) above the score, thus indicating the major milestones, and effectively marking four movements, each of several sections. The first five minutes of the music can thus be regarded as an extended prelude, setting the scene, in which recurring motifs are introduced.

The first quotation (track 2) is from Theocritus: ‘Ay, but she too came, the sweetly smiling Cypris, craftily smiling she came, yet keeping her heavy anger'. Bantock marks the music liberamente and launches a long lyrical passage taken by violins in octaves; this rises to a climax, like waves breaking on a rock, and then falls quiet again. Now follows a quotation from the Smyrna Pastoral poet Bion: ‘Mild Goddess, in Cypris born—why art thou thus vexed with mortals and immortals?' (track 3). Bantock's marking is animando, and the texture of repeated quavers in the strings reminds us of his friend Sibelius. This is sea-music in the tradition of his earlier Hebridean Symphony and leads to a passage of repeated fanfaring trumpets reminiscent of the climax of that work. Eventually the storm subsides and quiet music leads to a violin solo launching the third section.

As the solo violin plays above a hushed accompaniment of muted strings (track 4) we have another quotation from Bion: ‘Great Cypris stood beside me while still I slumbered'. The tempo marking is lentamente; Bantock's dream is of romance and the exotic as he soon presents a wide-spanning string tune and then contrasts it with oriental dances at first delicate, then much wilder. The opening cello and double-bass motif returns on clarinet and Bantock launches into glowing and triumphant orchestral love music and his fourth quotation, from Bion's pupil Moschus: ‘His prize is the kiss of Cypris, but if thou bringest Love, not the bare kiss, O stranger, but yet more shalt thou win' (track 5). The end is happy and affirmative, the material from the opening returns, no longer questioning but heroic and confident, and eventually with a quiet sunset epilogue Bantock's vision fades from sight.

This may have been a strange work to have written at the turn of 1938/9, yet Bantock's dream of Aphrodite and of a happier time is vivid and gripping, as Scheherazade-like he evokes an antique world. It is now almost a cliché to refer to the Freudian imagery of the sea, yet it is surely no accident that as the seventy-year-old composer's thoughts are of love and his earlier life, he finds his most compelling metaphor in thrilling sea music. As his liner crosses the Pacific the final sunset glow is for the moment without any hint of the war and the horrors so soon to come.

Lewis Foreman © 1995

Bantock: The Cyprian Goddess, Dante And Beatrice / Handley

Release Date: 11/21/1995

Label: Hyperion Catalog #: 66810 Spars Code: DDD

Composer: Granville Bantock

Conductor: Vernon Handley

Orchestra/Ensemble: Royal Philharmonic Orchestra

Number of Discs: 1

Recorded in: Stereo

Length: 1 Hours 9 Mins.

Works on This Recording

1. Symphony no 3 "The Cyprian Goddess" by Granville Bantock

Conductor: Vernon Handley

Orchestra/Ensemble: Royal Philharmonic Orchestra

Period: 20th Century

Written: 1938/1939; England

Date of Recording: 05/1995

Length: 24 Minutes 23 Secs.

2. Variations for Orchestra on the theme HFB "Helena Variations" by Granville Bantock

Conductor: Vernon Handley

Orchestra/Ensemble: Royal Philharmonic Orchestra

Period: 20th Century

Written: 1899; England

Date of Recording: 05/1995

Length: 19 Minutes 25 Secs.

3. Dante and Beatrice by Granville Bantock

Conductor: Vernon Handley

Orchestra/Ensemble: Royal Philharmonic Orchestra

Period: 20th Century

Written: 1901/1910; England

Date of Recording: 05/1995

Length: 25 Minutes 0 Secs.

Notes and Editorial Reviews

'Hyperion's third collection of orchestral works by Sir Granville Bantock, a composer who rivalled Elgar in his day, is quite simply superb' (The Scotsman)

'Outstanding. A sumptuous wallow for all unashamed Romantics' (BBC Music Magazine)

'Full marks, Hyperion - now we can all wallow once more. Worth the price for the sumptuous sound alone!' (BBC Music Magazine)

'Just as good as its predecessors. Roundly recommended' (Fanfare, USA)

'The finest large symphonic recordings of the decade. The burnished colors of Bantock's singular music - moody, quirky, haunting - glow under the direction of Vernon Handley' (Fi, USA)

Pressestimmen

I. Lace im BBC Music Magazin 1 / 96: "Diese Ver- öffentlichung ist herausragend: ein Schwelgen in unverhohlener Romantik. Alle drei Stücke bezeugen Bantocks Meisterschaft der Orchester- behandlung, besonders sein markanter vielstim- miger Blechbläser-Satz. Handley und das RPO lieben dieses Repertoire hörbar und musizieren mit Inbrunst und Virtuosität."

Product-Information:

Sir Edward Elgar described Bantock as having ‘the most fertile musical brain of our time'. The Cyprian Goddess, Bantock's Third Symphony, was written as he crossed the Pacific Ocean. The music plays continuously, but consists of a variety of contrasting sections, and the feeling of a story or succession of images is striking. Bantock's dream of Aphrodite and of a happier time is vivid and gripping. The world-famous Royal Philharmonic Orchestra and Vernon Handley here see their third in a series of Bantock recordings, all of which have met with consistent praise.

Introduction

The Edwardian period, and indeed the late 1890s, is fascinating for the student of British music. It saw the first appearance of what we now know as an extended repertoire of distinctively English music (even though the composers of much of it were in fact Irish or Scottish and some of the landscape that inspired them was on the Welsh border!). The big name as far as we are concerned was, of course, Elgar. But at a time when provincial centres of music were of major importance, Granville Bantock, associated with Birmingham from 1900 to 1934, was regarded by some as comparable with Elgar. It was Neville Cardus, no less, who wrote: ‘Those of us who were then “young” and “modern” regarded Bantock as of much more importance than Elgar … Bantock was definitely “contemporary”.' Indeed it was Elgar himself who referred to Bantock as ‘having the most fertile musical brain of our time'.

Bantock first achieved fame as a conductor and as the champion of his British contemporaries, though it was not only British music that he pioneered. In particular, he was an early advocate of Sibelius and is the dedicatee of the Finnish master's Third Symphony. Soon he was also known as a fluent composer of considerable individuality.

Bantock was born in London in 1868, the son of a well-known surgeon. His youthful passion for music parallels the story familiar from the lives of many composers—of overcoming parental opposition. In Bantock's case his father's chosen career for him was the Indian Civil Service, and later, chemical engineering. Music, of course, prevailed and in 1888 he spent a summer holiday in Germany soaking up Tristan and Parsifal, and then started at the Royal Academy of Music as a composition pupil of Frederick Corder contemporary with Joseph Holbrooke. Corder would later teach Bax, York Bowen and Eric Coates, among many others.

Music poured from the young Bantock and though at first both Tchaikovsky and Strauss were noticeable as models, a very personal use of both voices and the orchestra enabled him to establish himself during the first decade of the century as an individual composer of personality and stature. Bantock was an illustrator in music. He was never lost for an apt musical image, and at his peak produced many arresting, colourful scores. This was when he was working on his massive setting of the complete text of Fitzgerald's Omar Khayyám, and the music he wrote at this time shares Omar's teeming invention and flamboyant scoring for both voices and orchestra. Between 1900 and 1914 Bantock produced, counting the three parts of Omar Khayyám separately as they were performed, seven extended works for chorus and orchestra, two extended orchestral song cycles (a third was orchestrated later), and more than a dozen colourful orchestral scores as well as voluminous songs and choral music.

After the First World War a new generation of brilliant composers emerged and Bantock began to appear old hat; indeed, by the time of the Second World War he was widely regarded as a ‘has been' by the younger generation, and if it had not been for the efforts of Cyril Neil, the managing director of the publisher Paxton, he would have had no encouragement and little income. Neil issued many short works that he specially commissioned on Paxton's own record label—really just a mood-music catalogue. While it included one or two fine works such as the Celtic Symphony and the frankly Sibelian Four Chinese Landscapes, the general critical effect was to underline how Bantock the composer had become a back number. Certainly it was no time to be making long-term assessments. Only now with the perspective of over fifty years and the advantage of fine performances can Bantock's quality, and the colour and personality of his music be fully appreciated.

Bantock gained considerable experience during 1894/5 conducting one of George Edwardes's variety companies on a world tour, particularly featuring Sydney Jones's A Gaiety Girl. On his return he was appointed Director of Music to the Tower Orchestra, New Brighton (a then fashionable resort across the Mersey from Liverpool) from 1897, where his expansion of the band and championship of British and other contemporary music won him a national reputation. In 1900 he secured the post of Principal of the Midland School of Music in Birmingham and in 1908 he succeeded Elgar as Peyton Professor of Music at Birmingham University. He was thus firmly established as a figurehead of British music outside London.

The twentieth century was a notable time for the development of the British symphony (indeed all symphonies). Paradoxically it was also the time when the avant-garde of succeeding generations solemnly informed us that the symphony was dead—and then went on to revitalize it in many startling ways! Bantock's first attempt at a symphony was probably a student exercise; a Symphony in C (1888) of which the full-score manuscript of a first movement and a scherzo and trio survives. Later came the Hebridean (1915/16) and Pagan (1923–1928) symphonies, and after these The Cyprian Goddess (1938/9) and the Celtic Symphony (1940). Bantock also used the term ‘symphony' for several vocal works, though he obviously did not consider them as forming part of any symphonic cycle or he would not have enumerated The Cyprian Goddess as number three. The first was Cedric and Aelfrida, subtitled ‘a dramatic symphony for orchestra and four voices', a sort of concert opera, dated 20 August 1892 and written when he was still a student. Later came Christus, ‘a festival symphony in ten parts'—a vast choral cycle that was never finished. Perhaps most intriguing were the choral symphonies for huge unaccompanied choirs written at the height of his powers before the First World War. These were Atalanta in Calydon (dated 29 September 1911), Vanity of Vanities (1913) and A Pageant of Human Life (3 August 1913). There are also a few sketches for an aborted Ossianic Symphony for voice and accompaniment. So Bantock was not only involved in the symphony as a form but also took the widest and most all-embracing view of what constituted the symphony. ‘The symphony must be like the world. It must embrace everything', Mahler is reputed to have said to Sibelius in a celebrated aphorism, a view to which Bantock must surely have subscribed.

One March afternoon in 1896 the twenty-eight-year-old Helena von Schweitzer called to have tea with an old lady. There was a third guest: ‘His head was leonine, with its massive formation and tawny colouring, and his eyes were remarkable, scintillating with vivid life, windows to an intense inner existence. He was massive in build also, and golden-bearded at a time when all the fashionable men-about-town were moustachioed with monotonous regularity.' Thus Granville Bantock's future wife later remembered how she first met her husband. She went on to describe his polymath interests: ‘The talk was as unconventional as the surroundings were prosaic. It fell on the ears of one listener like the sound of water on a parched land. Science, literature, art and travel were discussed in a broad-minded spirit, very foreign to that period of many taboos. The hostess drew the shy listener into the conversation, and at the end of this miniature symposium, she found herself committed to the task of writing thirty-six lyrics, to be set to music by the young composer, for such he was' … ‘On a slip of paper he sketched out his scheme for a series of thirty-six Songs of the East, each set of six to be devoted to an oriental country. He would provide books on the subject, further discussion was arranged for the following week, and the whole was completed with tornado-like swiftness which soon became familiar.'

They were married in 1898, and the following year he wrote Helena, variations on a theme derived from the initials of his wife's name (HFB: in German musical notation, B natural, F, B flat). The piano score is dated 27 October 1899; Granville and Helena were both thirty-one. In less than a year the music was published by Breitkopf & Härtel. Printed on the flyleaf the composer wrote: ‘Dearest Wife! Accept these little Variations with all my heart's love. They are intended as an expression of my thoughts and reflections on some of your moods during a wearisome absence from each other.'

Elgar's Enigma Variations had been first performed in London on 19 June 1899 and created a great stir. Bantock had invited Elgar to conduct a concert with his orchestra at New Brighton, and soon afterwards Edward and Alice Elgar (not yet Lady Elgar) came to stay; Elgar's wife would have been fifty. Helena Bantock noted with astonishment ‘no less than seven hot water bottles being filled for his bed, on the occasion of Elgar complaining of a slight chill'. On 16 July Elgar conducted the concert, including Enigma, and one cannot imagine Bantock being other than thrilled. It seems highly probable that Bantock then impulsively set out to write his own variations, albeit based Pauline-like on his wife's moods rather than his various friends. It was his first orchestral work in his mature style. Could it be that in emulating Elgar by ending in high spirits it was not only Helena he was celebrating in the Finale. First performed in Antwerp on 21 February 1900 where Bantock had been asked to conduct a concert of British music, the Variations received their first British performance, conducted by the composer, on 25 March in the Philharmonic Hall Liverpool.

Dante and Beatrice was originally written (as Tone Poem No 2) in the summer of 1901 and performed at New Brighton and also in Birmingham at a Halford Concert. A commentator on the first version, which is now lost, pointed out that when Bantock revised it (the new score is dated 31 July 1910), little alteration was made in the music apart from the blending of the sections into a continuous fabric. The early version was in six sections, and it may be helpful to have the titles as a guide to the main episodes in the later version. These were: ‘Dante', ‘Strife of Guelphs and Ghibellines', ‘Beatrice', ‘Dante's vision of Hell, Purgatory and Heaven', ‘Dante's exile', and ‘Death'. In the revision of 1910 recorded here, Bantock styles his score a ‘psychological study' intending to evoke states of mind rather than describe individual episodes in detail.

The music opens with an introduction which presents the two important themes—Dante's quietly in unison and, after a climax, Beatrice's theme appears against a yearning extension of Dante's motif. The themes are developed as finally they are combined. At the climax of the development the music becomes wilder—firmly based on diminished sevenths—with a cataclysmic outburst, the depiction of the ‘Vision of Hell, Purgatory and Heaven' in the earlier version. This leads to the extended lyrical closing section of the work, the chromatic harmony and brilliant handling of a large orchestra creating an ecstatic mood distinctive of its time. Soon Dante hears of Beatrice's death (‘poignant grief') and dies still transfigured by his love for her. Dedicated ‘To my friend Henry J Wood', the score is prefaced by the quotation ‘L'amor che move il sole e l'altre stelle' (‘The love that moves the sun and the other stars') from Il Paradiso. The first performance was at Queen's Hall on 24 May 1911 during the London Music Festival in the Coronation season. It cannot have been entirely satisfactory for Bantock as it was the same concert in which Elgar's Second Symphony was first heard. Ticket prices were sky-high and the critics were there to hear Elgar—about whom they wrote at length—and not his illustrious Birmingham contemporary.

After the War Bantock remained in Birmingham until 1934, composing a variety of works and in particular briefly achieving some celebrity for his two vast choral works The Song of Songs (broadcast on 11 December 1927) and Pilgrim's Progress (commissioned by the BBC a couple of years later), the latter before Vaughan Williams was generally associated with Bunyan or Pilgrim. However, Bantock's new works were less and less heard in concerts and were no longer seen as representing the new. Though the Pagan Symphony was first performed in 1936, Bantock's star as a composer was no longer in the ascendant in spite of his knighthood in 1934.

In the 1930s he undertook examining tours overseas for Trinity College of Music and it was while on one of these that he wrote the The Cyprian Goddess, his third symphony, which he subtitled ‘Aphrodite in Cyprus'. Written while crossing the Pacific, the manuscript full score is dated ‘12 January 1939 Pacific Ocean. Suva (Fiji)'.

Bantock's love affair with languages led him to study not only Latin and Greek, but also Persian. The Pagan Symphony had taken its cue from the second book of Horace's Odes, and the opening of Ode XIX concerning Bacchus. Aphrodite is, of course, the Goddess of Love, whom he had invoked so memorably before in the Sappho Songs for contralto and orchestra. Now in The Cyprian Goddess he prefaces the score with the two Latin verses of Ode XXX in the first book, as well as a photograph of the statue of the Venus de Milo from the Louvre.

O Venus regina Cnidi Paphique

Sperne dilectam Cypron et vocantis

Ture te multo Glycerae decoram

Transfer in aedem.

Fervidus tecum puer et solutis

Gratiae zonis properentque Nymphae

Et parum comis sine te Juventas

Mercuriusque.

Venus, queen of Knidos and Paphos,

quit thy favoured Cyprus and come

to the fine temple of Glycera which

calls you with much incense.

Let the passionate child, the Graces

with their girdles untied, the nymphs,

Youth, all the less attractive without you,

and Mercury hasten with you.

The music plays continuously, but consists of a variety of contrasting sections, and the feeling of a story or succession of images is striking. Why Bantock was never commissioned to compose for the films when he writes so cinematographically is a mystery. Bantock gives us no detailed programme, but from time to time he writes a classical quotation (in English translation) above the score, thus indicating the major milestones, and effectively marking four movements, each of several sections. The first five minutes of the music can thus be regarded as an extended prelude, setting the scene, in which recurring motifs are introduced.

The first quotation (track 2) is from Theocritus: ‘Ay, but she too came, the sweetly smiling Cypris, craftily smiling she came, yet keeping her heavy anger'. Bantock marks the music liberamente and launches a long lyrical passage taken by violins in octaves; this rises to a climax, like waves breaking on a rock, and then falls quiet again. Now follows a quotation from the Smyrna Pastoral poet Bion: ‘Mild Goddess, in Cypris born—why art thou thus vexed with mortals and immortals?' (track 3). Bantock's marking is animando, and the texture of repeated quavers in the strings reminds us of his friend Sibelius. This is sea-music in the tradition of his earlier Hebridean Symphony and leads to a passage of repeated fanfaring trumpets reminiscent of the climax of that work. Eventually the storm subsides and quiet music leads to a violin solo launching the third section.

As the solo violin plays above a hushed accompaniment of muted strings (track 4) we have another quotation from Bion: ‘Great Cypris stood beside me while still I slumbered'. The tempo marking is lentamente; Bantock's dream is of romance and the exotic as he soon presents a wide-spanning string tune and then contrasts it with oriental dances at first delicate, then much wilder. The opening cello and double-bass motif returns on clarinet and Bantock launches into glowing and triumphant orchestral love music and his fourth quotation, from Bion's pupil Moschus: ‘His prize is the kiss of Cypris, but if thou bringest Love, not the bare kiss, O stranger, but yet more shalt thou win' (track 5). The end is happy and affirmative, the material from the opening returns, no longer questioning but heroic and confident, and eventually with a quiet sunset epilogue Bantock's vision fades from sight.

This may have been a strange work to have written at the turn of 1938/9, yet Bantock's dream of Aphrodite and of a happier time is vivid and gripping, as Scheherazade-like he evokes an antique world. It is now almost a cliché to refer to the Freudian imagery of the sea, yet it is surely no accident that as the seventy-year-old composer's thoughts are of love and his earlier life, he finds his most compelling metaphor in thrilling sea music. As his liner crosses the Pacific the final sunset glow is for the moment without any hint of the war and the horrors so soon to come.

Lewis Foreman © 1995

Bestell-Nr.:

Hyperion 66810A

Lieferzeit:

Sofort bestellen | Anfragen | In den Warenkorb

Verwandte Artikel

Verkäufer/in dieses Artikels

Verkäufer/in

KLASSIK-KENNER

(Niederlande,

Antiquariat/Händler)

Alle Angebote garantiert lieferbar

>> Benutzer-Profil (Impressum) anzeigen

>> AGB des Verkäufers anzeigen

>> Verkäufer in die Buddylist

>> Verkäufer in die Blocklist

Angebote: Tonträger (12005)

>> Zum persönlichen Angebot von KLASSIK-KENNER

Alle Angebote garantiert lieferbar

>> Benutzer-Profil (Impressum) anzeigen

>> AGB des Verkäufers anzeigen

>> Verkäufer in die Buddylist

>> Verkäufer in die Blocklist

Angebote: Tonträger (12005)

>> Zum persönlichen Angebot von KLASSIK-KENNER

Angebotene Zahlungsarten

- Banküberweisung (Vorkasse)

Ihre allgemeinen Versandkosten

| Allgemeine Versandkosten gestaffelt nach Anzahl | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Landweg | Luftweg | |||||

| Anzahl | Niederlande | Niederlande | EU | Welt | EU | Welt |

| bis 2 | 5,00 € | 5,00 € | 10,00 € | 10,00 € | 10,00 € | 12,00 € |

| bis 4 | 7,00 € | 7,00 € | 15,00 € | 15,00 € | 15,00 € | 15,00 € |

| bis 8 | 7,00 € | 7,00 € | 20,00 € | 20,00 € | 20,00 € | 20,00 € |

| darüber | 10,00 € | 10,00 € | 25,00 € | 40,00 € | 25,00 € | 40,00 € |

| Landweg | Luftweg | |||||

| Niederlande | Niederlande | EU | Welt | EU | Welt | |

| pauschal ab 29,00 € | 10,00 € | 10,00 € | 15,00 € | 25,00 € | 20,00 € | 40,00 € |