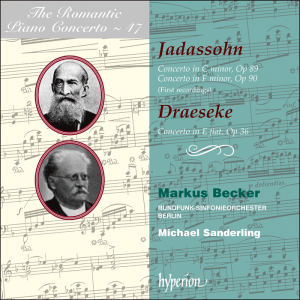

Jadassohn / Draeseke: Klavierkonzerte / Markus Becker, Michael Sanderling, Berlin R.S.O. – Tonträger gebraucht kaufen

Möchten Sie selbst gebrauchte Tonträger verkaufen? So einfach geht's …

Verkäufer-Bewertung:

100,0% positiv (582 Bewertungen)

dieser Tonträger wurde bereits 1 mal aufgerufen

dieser Tonträger wurde bereits 1 mal aufgerufen

Versandkosten: 10,00 € (Deutschland)

gebrauchter Tonträger

* Der angegebene Preis ist ein Gesamtpreis. Gemäß §19 UStG ist dieser Verkäufer von der Mehrwertsteuer befreit (Kleinunternehmerstatus).

Dieser Artikel ist garantiert lieferbar.

Künstler/in:

EAN:

Label:

Hyperion,DDD,2008

Zustand:

wie neu

Spieldauer:

70 Min.

Jahr:

2009

Format:

CD

Gewicht:

120 g

Beschreibung:

Album: NEU und EINGESCHWEISST (OVP). NEW and SEALED.

The Romantic Piano Concerto Vol 47 - Draeseke, Jadassohn / Becker

Release Date: 03/10/2009

Label: Hyperion Catalog #: 67636 Spars Code: DDD

Composer: Salomon Jadassohn, Felix Draeseke

Performer: Markus Becker

Conductor: Michael Sanderling

Orchestra/Ensemble: Berlin Radio Symphony Orchestra

Number of Discs: 1

Recorded in: Stereo

Length: 1 Hours 9 Mins.

Works on This Recording

1. Concerto for Piano no 1 in C minor, Op. 89 by Salomon Jadassohn

Performer: Markus Becker (Piano)

Conductor: Michael Sanderling

Orchestra/Ensemble: Berlin Radio Symphony Orchestra

Period: Romantic

Date of Recording: 01/2008

Venue: Jesus-Christus-Kirche, Berlin, Germany

2. Concerto for Piano no 2 in F minor, Op. 90 by Salomon Jadassohn

Performer: Markus Becker (Piano)

Conductor: Michael Sanderling

Orchestra/Ensemble: Berlin Radio Symphony Orchestra

Period: Romantic

Date of Recording: 01/2008

Venue: Jesus-Christus-Kirche, Berlin, Germany

3. Concerto for Piano in E flat major, Op. 36 by Felix Draeseke

Performer: Markus Becker (Piano)

Conductor: Michael Sanderling

Orchestra/Ensemble: Berlin Radio Symphony Orchestra

Period: Romantic

Written: 1885-1886; Dresden, Germany

Date of Recording: 01/2008

Venue: Jesus-Christus-Kirche, Berlin, Germany

Notes and Editorial Reviews

These glittering, virtuoso concertos make welcome additions to Hyperion's "Romantic Piano Concerto" series (now at 47 volumes!). Salomon Jadassohn was a respected Leipzig pedagogue whose music vanished without a trace after his death in 1902, assisted by the fact that he was Jewish and so lost whatever support he may have had in his German homeland. Felix Draeseke, on the other hand, was strikingly successful during his own lifetime, so the neglect he has suffered since is a bit harder to explain. It may have something to do with the fact, as note-writer Kenneth Hamilton points out, that neither concerto sports an instantly memorable tune, but he goes too far in trying to defend these works at the expense of Grieg and Brahms--there's no need to tear down a certified masterpiece to build up the work of an unknown.

Jadassohn's two concertos are compact (15 and 23 minutes respectively), full of Lisztian fireworks, formally experimental, and a great deal of fun. Draeseke was one of many German composers who straddled the Wagner and Brahms camps, which is probably why he fell between the cracks historically. But he marries elements of both schools together very effectively, and if his handling of form is more traditional and the thematic material not perhaps instantly memorable, the work as a whole makes for very satisfying listening. Markus Becker's confident, technically adroit performances certainly make the best possible case for all three works, and he receives excellent support from Michael Sanderling and the Berlin Radio orchestra. Typically fine sound guarantees collectors of this series complete satisfaction, while novice listeners interested in good Romantic music should consider this strongly as well. Recommended without reservations.

--David Hurwitz, ClassicsToday.com

Review by James Leonard [-]

If you've worked your way through the entire standard repertory of Romantic piano concertos and are eager for more, then you may be ready for these concertos by Salomon Jadassohn and Felix Draeseke. The former may be best known as the teacher of Grieg and Delius and the latter for composing the gargantuan Christus oratorio, but they also wrote in the concerto form and the results of their efforts are released for the first time here performed by pianist Markus Becker with the Rundfunk-Sinfonieorchester Berlin under Michael Sanderling. All three works were written between 1885 and 1887, and all three are built on the same pillars as the more familiar concertos from the era: big themes, colorful orchestration, and heroic virtuosity for the soloist. Jadassohn's two concertos, the first in C minor and the second in F minor, are more musically conservative, with less chromaticism and tighter forms, while Draeseke's E flat major Concerto is more modern, with richer harmonies and more expansive forms. Becker does both composers justice with his full tone, crisp articulation, and robust technique, and the Berlin orchestra under Sanderling supports him with strong playing. If none of these works challenge the great Romantic concertos in terms of beauty or profundity, they are at least well-composed and sincere works given well-thought-out and earnest performances recorded in warm, detailed, digital sound.

'The busy piano-writing in these two world premieres is brilliant and passionate, the scoring [Jadassohn] is textbook 1887 and the musical structure inventive … Hyperion's A-team for concertos (Andrew Keener and Simon Eadon) is on top form, while the Berlin orchestra and Michael Sanderling provide crisp support for the sparkling and industrious Markus Becker who leaves the impression not only of having an affection for the three works but also that he has been playing them all his life' (Gramophone)

'Altogether an enjoyable disc for those who would explore the unfrequented byways of Romanticism' (BBC Music Magazine)

'These pieces, which burst with … memorable tunes and lashings of showy arpeggios, are played with admirable swagger by Markus Becker and are a welcome addition to Hyperion's exhaustive study of the Romantic Piano Concerto' (The Observer)

'It's clear Becker really feels this music… and I have a feeling you'll want to go back and play it again!' (American Record Guide)

'There is much to enjoy here: the nobility of the second movement of the Jadassohn First, the bucolic energy of the finale of his Second, the rollocking finale of the Draeseke … Becker's confident playing and tonal richness make as persuasive a case for the music as could reasonably be expected' (International Record Review)

'Sonics are first rate, as usual with Hyperion. Let's hear it for obscure piano concertos!' (Audiophile Audition, USA)

'Markus Becker delivers heroic accounts of all three concertos, and Michael Sanderling's Berlin musicians bring buoyant orchestral textures to the mix' (International Piano)

'Markus Becker's confident, technically adroit performances certainly make the best possible case for all three works, and he receives excellent support from Michael Sanderling and the Berlin Radio orchestra. Typically fine sound guarantees collectors of this series complete satisfaction, while novice listeners interested in good Romantic music should consider this strongly as well. Recommended without reservations' (ClassicsToday.com)

'The performances are all that one could expect, the music shown in the best possible light. Markus Becker is both virtuoso and musician' (ClassicalSource.com)

Produktinfo

Die Romantischen Klavierkonzerte Vol. 45

Die neueste Folge der »Romantischen Klavierkonzerte« präsentiert Klavierkonzerte von Salomon Jadassohn (1831–1902) und Felix Draeseke (1835–1913), die zu den führenden deutschen Komponisten in der zweiten Hälfte des 19. Jahrhunderts zählten, heute aber kaum mehr bekannt sind. Beide begannen ihre Studien am Leipziger Konservatorium, waren Schüler von Franz Liszt, Anhänger der »Neuen Deutschen Schule« und unterrichteten später an Musikkonservatorien. Ihre Klavierkonzerte entstanden ungefähr in der gleichen Zeit Ende der 1880er Jahre, musikalisch ist die Nähe zu ihrem Lehrer Liszt unverkennbar.

Product-Information:

Though barely remembered now, both Salomon Jadassohn and Felix Draeseke were major figures in German musical life in the second half of the 19th century. Both began their studies at the conservative Leipzig Conservatory but after independently encountering Liszt and his work at Weimar in the 1850s both became disciples of that composer and the New German School he established. Jadassohn subsequently returned to Leipzig where he composed and had a long and distinguished teaching career, his pupils including Delius, Grieg and Busoni, while Draeseke finally ended up in Dresden teaching at the Conservatory there.

In a further paralleling of lives, both composers' concertos were written at almost the same time—Draeseke's sole example in 1886 and Jadassohn's two the following year. All three are expertly crafted and feature wonderfully idiomatic piano writing, as one would expect of Liszt pupils. Stylistically they show their links both to Liszt's single movement forms (Jadassohn 1) and also to more traditional models. While not ground-breaking these are thoroughly enjoyable examples of the genre and one must question why the Jadassohn works in particular, which have truly memorable themes, have been so completely forgotten.

We are delighted to welcome Markus Becker in his first concerto recording for Hyperion; expect more soon!

Introduction

Felix Draeseke (1835–1913) and Salomon Jadassohn (1831–1902) were two of the more interesting also-rans of Romantic music. Although Jadassohn was ultimately remembered as the teacher of an amazing array of celebrated pupils—including Edvard Grieg, Frederick Delius and Ferruccio Busoni—Draeseke was a force to be reckoned with in his own right. He was even touted as a serious rival to Brahms as a symphonist, and boldly emulated Wagner with an astonishingly ambitious sacred counterpart to the Ring cycle—a collection of choral works entitled Christus: A Mystery in three Oratorios with a Prelude. This mammoth undertaking was to be performed over several days, with a ‘preliminary evening' thrown in for good measure. Its first performance in 1912 was a glittering triumph for its industrious composer, but the sheer length of the work, combined with the oratorio genre's rapid falling out of fashion in the twentieth century, put paid to any chance of sustained success. Few have now heard a note of Christus, and it seems unlikely to overtake Wagner's Ring in popular affection any time soon.

But it was initially Draeseke's orchestral and instrumental music that was most admired. His Piano Sonata ‘quasi fantasia' (1867) earned plaudits from no less a figure than Franz Liszt, who considered it to be one of the most impressive of the modern era. (Those who are skeptical about this judgment should seek out a chance to listen to it themselves—it really is a fascinating work.) Draeseke had by then long been an adherent of the ‘New German School' of Liszt and Wagner, despite his initial training at the notoriously conservative Leipzig Conservatory. Bowled over by hearing Liszt's performances of Wagner's Lohengrin in Weimar, he himself took up residence in the small town in 1856, there to imbibe the ‘music of the future' and participate in the lively artistic life surrounding Liszt. His reverence for Liszt was typically manifested in the composition of symphonic poems after the model of his master. Almost needless to say, the shadow of Richard Wagner fell heavily over his first attempt at opera, the title of which—König Sigurd—immediately betrays its influences. It was, in fact, one of the earliest of those depressingly numerous Wagner-imitations that young German composers had to get out of their system before acquiring their own individuality. Even Richard Strauss went through his own copycat phase with his first opera Guntram, where a forlorn knight mooches around, predictably seeking some sort of ill-defined ‘redemption' in a manner that suggests an all-too-close study of Wagner's Parsifal.

Draeseke's respect for Wagner was not reciprocated. The latter seems to have thought little of Draeseke's music, describing the Germania March—perhaps the only work by Draeseke that Wagner had ever heard performed—as ‘pitiful'. Draeseke, for his part, became gradually more disaffected with the New German School, a process accelerated by his deep disapproval of Wagner's affair with Liszt's daughter Cosima. He noticeably began to plough a more musically conservative furrow after settling in Dresden in 1876. In 1884 he was officially enlisted to the staff of the city's Royal Saxon Conservatory, and spent the remaining decades of his life there. His interests turned increasingly towards sacred choral music, often pervaded by ostentatiously contrapuntal textures of a more conservative style. Liszt was not impressed. On hearing some of Draeseke's later church music, he commented acidly, ‘it seems our lion has turned into a rabbit!'.

Draeseke's three-movement Piano Concerto in E flat major Op 36 was composed in 1885–6, and clearly demonstrates the more traditional elements creeping stealthily into the music of this erstwhile lion of the avant-garde. The Adagio slow movement, a fairly straightforward set of variations on a hymn-like theme initially presented by the piano, harks virtually back to Beethoven. It is, indeed, rather obviously indebted to the similar slow movement of Beethoven's ‘Emperor' Concerto (in the same key as Draeseke's), without, alas, reaching the rapt intensity of the earlier master's music. The first variation, characterized by alternating figures in sixths, further reminds us that the later nineteenth century was also the era of Brahms, and those listeners who know the slow movement of Brahms's F minor Piano Sonata will notice some striking echoes here. But this remains the only Brahmsian allusion in the Concerto, for both the first movement, with its vigorously assertive principal theme, and the last movement, a rambunctious scherzo-finale in 6/8 time, confirm that Draeseke's model was certainly Beethoven. The quasi improvisatory dialogue between soloist and orchestra that so assertively opens the work once again has origins in the initial flourish of the ‘Emperor', and Beethoven's finale is also a rollicking movement in 6/8. Yet Draeseke's Concerto is hardly a slavish copy of his great predecessor's. The piano writing, with its plethora of alternating octaves and cascading chords, is very much in the late-Romantic style, and shows that Draeseke's years with Liszt in Weimar were not entirely wasted. The orchestration, too, is vivid and colourful. There is much to enjoy here, and even if the Concerto's melodic inspiration is ultimately not the equal of its slick craftsmanship, the piece as a whole hardly deserves the deep oblivion to which it has been consigned over the last hundred years.

‘Solid craftsmanship' seems indeed to have been the phrase most contemporary critics reached for when trying to give their impression of Salomon Jadassohn's music, a phrase that no doubt flowed more easily from their pen owing to his reputation as one of the Leipzig Conservatory's longest-serving composition teachers. Even surviving photographs of Jadassohn promote this image of the strict pedagogue, eyes staring out unwaveringly, sandwiched between a follicly challenged forehead and a correspondingly over-luxuriant beard. Jadassohn had himself enrolled as a student of the Conservatory in 1848, but eyebrows were raised at that august institution when it was discovered that he was occasionally slipping away to take lessons from the arch-enemy Liszt in Weimar. Indeed, despite his basically conservative tendencies, the prolific Jadassohn was somewhat influenced by the music of Liszt and Wagner, nowhere more obviously than in his Piano Concerto No 1 in C minor Op 89 (1887), which forsakes the traditional organization (heard, for example, in the Draeseke) in favour of an interlinked Introduction quasi recitativo, Adagio sostenuto and Ballade. In proportions this turns out to be very similar to Liszt's first piano concerto, with a relatively perfunctory, improvisatory opening section, a more expansive slow section and then a finale which emerges as the most complex and prolonged movement of all, unfolding in the full sonata-form that the other sections notably avoided. A frenetically agitated coda rounds off this passionate and formally inventive piece.

A certain imaginative approach to the usual formal structures is also evident in Jadassohn's Piano Concerto No 2 in F minor Op 90, composed—as the opus number would suggest—immediately after the first concerto. Jadassohn seems to have been inspired to write the second piece by the opportunities this offered to vary the formal outlines yet again. Here he composes a fairly standard but imposing Allegro energico first movement, in contrast to the fleetingly despairing recitative of Op 89—its grim, march-like main theme sounding to British ears rather like a minor-key version of ‘Men of Harlech'. The Allegro appassionato last movement, too, is in an extended sonata form, the coda this time turning to the major for the celebratory conclusion that Op 89 so signally failed to provide. It is the slow movement, however, that seems to toy most creatively with listeners' expectations. After a winsome Andantino quasi allegretto tune in A flat major presented by the piano, a short cadenza from the soloist leads into faster music, culminating in an Allegro deciso in F minor that sounds very much like it ought to be the beginning of the finale. The Andantino tune seems only to have been a modest introduction to the last movement—except that it isn't. The music slows down again, and the Andantino returns, finally fading out in a lazy haze of A flat arpeggios. Startlingly, the reverie is abruptly broken by a dramatic signal on the trumpets. Now we can really settle into our seats for the last movement—what went before was simply a gentle, and ingenious, deception.

Having listened to the concertos on this disc, we might pause to ask ourselves what went wrong, why three perfectly respectable, expertly written and reasonably inventive pieces should have been relegated to the dustbin of history after the deaths of their composers? After all, it is not as if every more famous work is a model of perfection. The first movement of Brahms's D minor Concerto seems to go on for ever once the listener realizes with horror that its composer intends to recapitulate the entire exposition note for note, and the Piano Concerto by Edvard Grieg joins its memorable melodies together by the musical equivalent of string and sticking plaster. Grieg's teacher Jadassohn is, at least in this respect, a much more accomplished operator. Two possible explanations offer themselves, the one artistic, the other political.

For all their compositional adroitness, both Draeseke and Jadassohn lacked the ability to invent tunes that are immediately pregnant with musical possibility, and which obstinately lodge in the mind of the listener. The opening of Brahms's D minor Concerto is so unforgettably stunning that one is prepared to forgive a certain long-windedness in its subsequent treatment, while Grieg's Concerto is quite simply a cornucopia of catchy tunes. They may not be flawless pieces, but they are certainly not bland. Furthermore, to Draeseke's and Jadassohn's disadvantage, not only was their musical material less initially arresting, but their works were dealt an unexpected blow by history. As a German-Jewish composer, Jadassohn was quite deliberately suppressed in the Germany of the 1930s. After the Nazi period was over, his name was firmly engraved in the list of ‘interesting historical figures' whose music was not well-enough known even to make a superficial judgment about its value. Draeseke's fate was more ironic. In stark contrast to Jadassohn's œuvre, his music was extolled by the Nazis as an example of ‘pure German art'. Indeed, the 1930s saw a mini Draeseke-revival, largely fuelled by official encouragement rather than grass-roots enthusiasm. After 1945 the inevitable reaction took place. Draeseke's music was tainted with political associations for which the hapless composer was hardly responsible. Once more he became a forgotten man. Around a century after their deaths, this recording finally gives listeners the opportunity to come to their own judgment of both composers.

Kenneth Hamilton © 2009

The Romantic Piano Concerto Vol 47 - Draeseke, Jadassohn / Becker

Release Date: 03/10/2009

Label: Hyperion Catalog #: 67636 Spars Code: DDD

Composer: Salomon Jadassohn, Felix Draeseke

Performer: Markus Becker

Conductor: Michael Sanderling

Orchestra/Ensemble: Berlin Radio Symphony Orchestra

Number of Discs: 1

Recorded in: Stereo

Length: 1 Hours 9 Mins.

Works on This Recording

1. Concerto for Piano no 1 in C minor, Op. 89 by Salomon Jadassohn

Performer: Markus Becker (Piano)

Conductor: Michael Sanderling

Orchestra/Ensemble: Berlin Radio Symphony Orchestra

Period: Romantic

Date of Recording: 01/2008

Venue: Jesus-Christus-Kirche, Berlin, Germany

2. Concerto for Piano no 2 in F minor, Op. 90 by Salomon Jadassohn

Performer: Markus Becker (Piano)

Conductor: Michael Sanderling

Orchestra/Ensemble: Berlin Radio Symphony Orchestra

Period: Romantic

Date of Recording: 01/2008

Venue: Jesus-Christus-Kirche, Berlin, Germany

3. Concerto for Piano in E flat major, Op. 36 by Felix Draeseke

Performer: Markus Becker (Piano)

Conductor: Michael Sanderling

Orchestra/Ensemble: Berlin Radio Symphony Orchestra

Period: Romantic

Written: 1885-1886; Dresden, Germany

Date of Recording: 01/2008

Venue: Jesus-Christus-Kirche, Berlin, Germany

Notes and Editorial Reviews

These glittering, virtuoso concertos make welcome additions to Hyperion's "Romantic Piano Concerto" series (now at 47 volumes!). Salomon Jadassohn was a respected Leipzig pedagogue whose music vanished without a trace after his death in 1902, assisted by the fact that he was Jewish and so lost whatever support he may have had in his German homeland. Felix Draeseke, on the other hand, was strikingly successful during his own lifetime, so the neglect he has suffered since is a bit harder to explain. It may have something to do with the fact, as note-writer Kenneth Hamilton points out, that neither concerto sports an instantly memorable tune, but he goes too far in trying to defend these works at the expense of Grieg and Brahms--there's no need to tear down a certified masterpiece to build up the work of an unknown.

Jadassohn's two concertos are compact (15 and 23 minutes respectively), full of Lisztian fireworks, formally experimental, and a great deal of fun. Draeseke was one of many German composers who straddled the Wagner and Brahms camps, which is probably why he fell between the cracks historically. But he marries elements of both schools together very effectively, and if his handling of form is more traditional and the thematic material not perhaps instantly memorable, the work as a whole makes for very satisfying listening. Markus Becker's confident, technically adroit performances certainly make the best possible case for all three works, and he receives excellent support from Michael Sanderling and the Berlin Radio orchestra. Typically fine sound guarantees collectors of this series complete satisfaction, while novice listeners interested in good Romantic music should consider this strongly as well. Recommended without reservations.

--David Hurwitz, ClassicsToday.com

Review by James Leonard [-]

If you've worked your way through the entire standard repertory of Romantic piano concertos and are eager for more, then you may be ready for these concertos by Salomon Jadassohn and Felix Draeseke. The former may be best known as the teacher of Grieg and Delius and the latter for composing the gargantuan Christus oratorio, but they also wrote in the concerto form and the results of their efforts are released for the first time here performed by pianist Markus Becker with the Rundfunk-Sinfonieorchester Berlin under Michael Sanderling. All three works were written between 1885 and 1887, and all three are built on the same pillars as the more familiar concertos from the era: big themes, colorful orchestration, and heroic virtuosity for the soloist. Jadassohn's two concertos, the first in C minor and the second in F minor, are more musically conservative, with less chromaticism and tighter forms, while Draeseke's E flat major Concerto is more modern, with richer harmonies and more expansive forms. Becker does both composers justice with his full tone, crisp articulation, and robust technique, and the Berlin orchestra under Sanderling supports him with strong playing. If none of these works challenge the great Romantic concertos in terms of beauty or profundity, they are at least well-composed and sincere works given well-thought-out and earnest performances recorded in warm, detailed, digital sound.

'The busy piano-writing in these two world premieres is brilliant and passionate, the scoring [Jadassohn] is textbook 1887 and the musical structure inventive … Hyperion's A-team for concertos (Andrew Keener and Simon Eadon) is on top form, while the Berlin orchestra and Michael Sanderling provide crisp support for the sparkling and industrious Markus Becker who leaves the impression not only of having an affection for the three works but also that he has been playing them all his life' (Gramophone)

'Altogether an enjoyable disc for those who would explore the unfrequented byways of Romanticism' (BBC Music Magazine)

'These pieces, which burst with … memorable tunes and lashings of showy arpeggios, are played with admirable swagger by Markus Becker and are a welcome addition to Hyperion's exhaustive study of the Romantic Piano Concerto' (The Observer)

'It's clear Becker really feels this music… and I have a feeling you'll want to go back and play it again!' (American Record Guide)

'There is much to enjoy here: the nobility of the second movement of the Jadassohn First, the bucolic energy of the finale of his Second, the rollocking finale of the Draeseke … Becker's confident playing and tonal richness make as persuasive a case for the music as could reasonably be expected' (International Record Review)

'Sonics are first rate, as usual with Hyperion. Let's hear it for obscure piano concertos!' (Audiophile Audition, USA)

'Markus Becker delivers heroic accounts of all three concertos, and Michael Sanderling's Berlin musicians bring buoyant orchestral textures to the mix' (International Piano)

'Markus Becker's confident, technically adroit performances certainly make the best possible case for all three works, and he receives excellent support from Michael Sanderling and the Berlin Radio orchestra. Typically fine sound guarantees collectors of this series complete satisfaction, while novice listeners interested in good Romantic music should consider this strongly as well. Recommended without reservations' (ClassicsToday.com)

'The performances are all that one could expect, the music shown in the best possible light. Markus Becker is both virtuoso and musician' (ClassicalSource.com)

Produktinfo

Die Romantischen Klavierkonzerte Vol. 45

Die neueste Folge der »Romantischen Klavierkonzerte« präsentiert Klavierkonzerte von Salomon Jadassohn (1831–1902) und Felix Draeseke (1835–1913), die zu den führenden deutschen Komponisten in der zweiten Hälfte des 19. Jahrhunderts zählten, heute aber kaum mehr bekannt sind. Beide begannen ihre Studien am Leipziger Konservatorium, waren Schüler von Franz Liszt, Anhänger der »Neuen Deutschen Schule« und unterrichteten später an Musikkonservatorien. Ihre Klavierkonzerte entstanden ungefähr in der gleichen Zeit Ende der 1880er Jahre, musikalisch ist die Nähe zu ihrem Lehrer Liszt unverkennbar.

Product-Information:

Though barely remembered now, both Salomon Jadassohn and Felix Draeseke were major figures in German musical life in the second half of the 19th century. Both began their studies at the conservative Leipzig Conservatory but after independently encountering Liszt and his work at Weimar in the 1850s both became disciples of that composer and the New German School he established. Jadassohn subsequently returned to Leipzig where he composed and had a long and distinguished teaching career, his pupils including Delius, Grieg and Busoni, while Draeseke finally ended up in Dresden teaching at the Conservatory there.

In a further paralleling of lives, both composers' concertos were written at almost the same time—Draeseke's sole example in 1886 and Jadassohn's two the following year. All three are expertly crafted and feature wonderfully idiomatic piano writing, as one would expect of Liszt pupils. Stylistically they show their links both to Liszt's single movement forms (Jadassohn 1) and also to more traditional models. While not ground-breaking these are thoroughly enjoyable examples of the genre and one must question why the Jadassohn works in particular, which have truly memorable themes, have been so completely forgotten.

We are delighted to welcome Markus Becker in his first concerto recording for Hyperion; expect more soon!

Introduction

Felix Draeseke (1835–1913) and Salomon Jadassohn (1831–1902) were two of the more interesting also-rans of Romantic music. Although Jadassohn was ultimately remembered as the teacher of an amazing array of celebrated pupils—including Edvard Grieg, Frederick Delius and Ferruccio Busoni—Draeseke was a force to be reckoned with in his own right. He was even touted as a serious rival to Brahms as a symphonist, and boldly emulated Wagner with an astonishingly ambitious sacred counterpart to the Ring cycle—a collection of choral works entitled Christus: A Mystery in three Oratorios with a Prelude. This mammoth undertaking was to be performed over several days, with a ‘preliminary evening' thrown in for good measure. Its first performance in 1912 was a glittering triumph for its industrious composer, but the sheer length of the work, combined with the oratorio genre's rapid falling out of fashion in the twentieth century, put paid to any chance of sustained success. Few have now heard a note of Christus, and it seems unlikely to overtake Wagner's Ring in popular affection any time soon.

But it was initially Draeseke's orchestral and instrumental music that was most admired. His Piano Sonata ‘quasi fantasia' (1867) earned plaudits from no less a figure than Franz Liszt, who considered it to be one of the most impressive of the modern era. (Those who are skeptical about this judgment should seek out a chance to listen to it themselves—it really is a fascinating work.) Draeseke had by then long been an adherent of the ‘New German School' of Liszt and Wagner, despite his initial training at the notoriously conservative Leipzig Conservatory. Bowled over by hearing Liszt's performances of Wagner's Lohengrin in Weimar, he himself took up residence in the small town in 1856, there to imbibe the ‘music of the future' and participate in the lively artistic life surrounding Liszt. His reverence for Liszt was typically manifested in the composition of symphonic poems after the model of his master. Almost needless to say, the shadow of Richard Wagner fell heavily over his first attempt at opera, the title of which—König Sigurd—immediately betrays its influences. It was, in fact, one of the earliest of those depressingly numerous Wagner-imitations that young German composers had to get out of their system before acquiring their own individuality. Even Richard Strauss went through his own copycat phase with his first opera Guntram, where a forlorn knight mooches around, predictably seeking some sort of ill-defined ‘redemption' in a manner that suggests an all-too-close study of Wagner's Parsifal.

Draeseke's respect for Wagner was not reciprocated. The latter seems to have thought little of Draeseke's music, describing the Germania March—perhaps the only work by Draeseke that Wagner had ever heard performed—as ‘pitiful'. Draeseke, for his part, became gradually more disaffected with the New German School, a process accelerated by his deep disapproval of Wagner's affair with Liszt's daughter Cosima. He noticeably began to plough a more musically conservative furrow after settling in Dresden in 1876. In 1884 he was officially enlisted to the staff of the city's Royal Saxon Conservatory, and spent the remaining decades of his life there. His interests turned increasingly towards sacred choral music, often pervaded by ostentatiously contrapuntal textures of a more conservative style. Liszt was not impressed. On hearing some of Draeseke's later church music, he commented acidly, ‘it seems our lion has turned into a rabbit!'.

Draeseke's three-movement Piano Concerto in E flat major Op 36 was composed in 1885–6, and clearly demonstrates the more traditional elements creeping stealthily into the music of this erstwhile lion of the avant-garde. The Adagio slow movement, a fairly straightforward set of variations on a hymn-like theme initially presented by the piano, harks virtually back to Beethoven. It is, indeed, rather obviously indebted to the similar slow movement of Beethoven's ‘Emperor' Concerto (in the same key as Draeseke's), without, alas, reaching the rapt intensity of the earlier master's music. The first variation, characterized by alternating figures in sixths, further reminds us that the later nineteenth century was also the era of Brahms, and those listeners who know the slow movement of Brahms's F minor Piano Sonata will notice some striking echoes here. But this remains the only Brahmsian allusion in the Concerto, for both the first movement, with its vigorously assertive principal theme, and the last movement, a rambunctious scherzo-finale in 6/8 time, confirm that Draeseke's model was certainly Beethoven. The quasi improvisatory dialogue between soloist and orchestra that so assertively opens the work once again has origins in the initial flourish of the ‘Emperor', and Beethoven's finale is also a rollicking movement in 6/8. Yet Draeseke's Concerto is hardly a slavish copy of his great predecessor's. The piano writing, with its plethora of alternating octaves and cascading chords, is very much in the late-Romantic style, and shows that Draeseke's years with Liszt in Weimar were not entirely wasted. The orchestration, too, is vivid and colourful. There is much to enjoy here, and even if the Concerto's melodic inspiration is ultimately not the equal of its slick craftsmanship, the piece as a whole hardly deserves the deep oblivion to which it has been consigned over the last hundred years.

‘Solid craftsmanship' seems indeed to have been the phrase most contemporary critics reached for when trying to give their impression of Salomon Jadassohn's music, a phrase that no doubt flowed more easily from their pen owing to his reputation as one of the Leipzig Conservatory's longest-serving composition teachers. Even surviving photographs of Jadassohn promote this image of the strict pedagogue, eyes staring out unwaveringly, sandwiched between a follicly challenged forehead and a correspondingly over-luxuriant beard. Jadassohn had himself enrolled as a student of the Conservatory in 1848, but eyebrows were raised at that august institution when it was discovered that he was occasionally slipping away to take lessons from the arch-enemy Liszt in Weimar. Indeed, despite his basically conservative tendencies, the prolific Jadassohn was somewhat influenced by the music of Liszt and Wagner, nowhere more obviously than in his Piano Concerto No 1 in C minor Op 89 (1887), which forsakes the traditional organization (heard, for example, in the Draeseke) in favour of an interlinked Introduction quasi recitativo, Adagio sostenuto and Ballade. In proportions this turns out to be very similar to Liszt's first piano concerto, with a relatively perfunctory, improvisatory opening section, a more expansive slow section and then a finale which emerges as the most complex and prolonged movement of all, unfolding in the full sonata-form that the other sections notably avoided. A frenetically agitated coda rounds off this passionate and formally inventive piece.

A certain imaginative approach to the usual formal structures is also evident in Jadassohn's Piano Concerto No 2 in F minor Op 90, composed—as the opus number would suggest—immediately after the first concerto. Jadassohn seems to have been inspired to write the second piece by the opportunities this offered to vary the formal outlines yet again. Here he composes a fairly standard but imposing Allegro energico first movement, in contrast to the fleetingly despairing recitative of Op 89—its grim, march-like main theme sounding to British ears rather like a minor-key version of ‘Men of Harlech'. The Allegro appassionato last movement, too, is in an extended sonata form, the coda this time turning to the major for the celebratory conclusion that Op 89 so signally failed to provide. It is the slow movement, however, that seems to toy most creatively with listeners' expectations. After a winsome Andantino quasi allegretto tune in A flat major presented by the piano, a short cadenza from the soloist leads into faster music, culminating in an Allegro deciso in F minor that sounds very much like it ought to be the beginning of the finale. The Andantino tune seems only to have been a modest introduction to the last movement—except that it isn't. The music slows down again, and the Andantino returns, finally fading out in a lazy haze of A flat arpeggios. Startlingly, the reverie is abruptly broken by a dramatic signal on the trumpets. Now we can really settle into our seats for the last movement—what went before was simply a gentle, and ingenious, deception.

Having listened to the concertos on this disc, we might pause to ask ourselves what went wrong, why three perfectly respectable, expertly written and reasonably inventive pieces should have been relegated to the dustbin of history after the deaths of their composers? After all, it is not as if every more famous work is a model of perfection. The first movement of Brahms's D minor Concerto seems to go on for ever once the listener realizes with horror that its composer intends to recapitulate the entire exposition note for note, and the Piano Concerto by Edvard Grieg joins its memorable melodies together by the musical equivalent of string and sticking plaster. Grieg's teacher Jadassohn is, at least in this respect, a much more accomplished operator. Two possible explanations offer themselves, the one artistic, the other political.

For all their compositional adroitness, both Draeseke and Jadassohn lacked the ability to invent tunes that are immediately pregnant with musical possibility, and which obstinately lodge in the mind of the listener. The opening of Brahms's D minor Concerto is so unforgettably stunning that one is prepared to forgive a certain long-windedness in its subsequent treatment, while Grieg's Concerto is quite simply a cornucopia of catchy tunes. They may not be flawless pieces, but they are certainly not bland. Furthermore, to Draeseke's and Jadassohn's disadvantage, not only was their musical material less initially arresting, but their works were dealt an unexpected blow by history. As a German-Jewish composer, Jadassohn was quite deliberately suppressed in the Germany of the 1930s. After the Nazi period was over, his name was firmly engraved in the list of ‘interesting historical figures' whose music was not well-enough known even to make a superficial judgment about its value. Draeseke's fate was more ironic. In stark contrast to Jadassohn's œuvre, his music was extolled by the Nazis as an example of ‘pure German art'. Indeed, the 1930s saw a mini Draeseke-revival, largely fuelled by official encouragement rather than grass-roots enthusiasm. After 1945 the inevitable reaction took place. Draeseke's music was tainted with political associations for which the hapless composer was hardly responsible. Once more he became a forgotten man. Around a century after their deaths, this recording finally gives listeners the opportunity to come to their own judgment of both composers.

Kenneth Hamilton © 2009

Bestell-Nr.:

Hyperion 67636A

Lieferzeit:

Sofort bestellen | Anfragen | In den Warenkorb

Verwandte Artikel

Verkäufer/in dieses Artikels

Verkäufer/in

KLASSIK-KENNER

(Niederlande,

Antiquariat/Händler)

Alle Angebote garantiert lieferbar

>> Benutzer-Profil (Impressum) anzeigen

>> AGB des Verkäufers anzeigen

>> Verkäufer in die Buddylist

>> Verkäufer in die Blocklist

Angebote: Tonträger (12005)

>> Zum persönlichen Angebot von KLASSIK-KENNER

Alle Angebote garantiert lieferbar

>> Benutzer-Profil (Impressum) anzeigen

>> AGB des Verkäufers anzeigen

>> Verkäufer in die Buddylist

>> Verkäufer in die Blocklist

Angebote: Tonträger (12005)

>> Zum persönlichen Angebot von KLASSIK-KENNER

Angebotene Zahlungsarten

- Banküberweisung (Vorkasse)

Ihre allgemeinen Versandkosten

| Allgemeine Versandkosten gestaffelt nach Anzahl | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Landweg | Luftweg | |||||

| Anzahl | Niederlande | Niederlande | EU | Welt | EU | Welt |

| bis 2 | 5,00 € | 5,00 € | 10,00 € | 10,00 € | 10,00 € | 12,00 € |

| bis 4 | 7,00 € | 7,00 € | 15,00 € | 15,00 € | 15,00 € | 15,00 € |

| bis 8 | 7,00 € | 7,00 € | 20,00 € | 20,00 € | 20,00 € | 20,00 € |

| darüber | 10,00 € | 10,00 € | 25,00 € | 40,00 € | 25,00 € | 40,00 € |

| Landweg | Luftweg | |||||

| Niederlande | Niederlande | EU | Welt | EU | Welt | |

| pauschal ab 29,00 € | 10,00 € | 10,00 € | 15,00 € | 25,00 € | 20,00 € | 40,00 € |